One of the qualities we look for in traditional art is cultural authenticity. By cultural authenticity, we mean that the traditional art object or performance faithfully represents the history, values, techniques, symbols, materials and forms of the culture within which this art has developed. When we believe that art objects or performances incorporate minimal influences from other cultures, we describe these as being genuine, as opposed to being derivative or copied or diluted. We seek out these “real” art experiences; our reward is the opportunity to dwell in other cultures and other times.

However, an honest appraisal of any art work created today will make it clear that all contemporary artists, even those working in traditional formats, are swayed by effects from all over the world. We are members of a global community flooded by global communication technology that transforms us in myriad, often unrealized, ways. There isn’t a corner of the earth, no matter how remote, that has not experienced contact with the rest of the world.

Cultural syncretism in art has always been with us, but the current breadth and speed of adaptation is unusual in human history. From the moment 10,000 or so years ago when a trader in Village A carried his community’s worked-leather goods to Village B on the other side of the mountain to exchange for their decorated pottery which he brought back to his own Village A, we have been having an impact on each other. We have shared forms, techniques, colors, symbols, sounds, images, usages, materials, cultural values, etc. from village to village, district to district, empire to empire, creating ever-larger cultural spheres of influence as the world grew ever smaller and we learned more and more about each other. Authentic, as in absolutely pure, has been totally lost to us for hundreds if not thousands of years. In the global marketplace, claims of authenticity have become a marketing ploy. Today we are a single cultural sphere, and there is no way of filtering out the weight of other cultures on our art-making. Today, all art is composed of a fusion of cultures. All art is cultural fusion art.

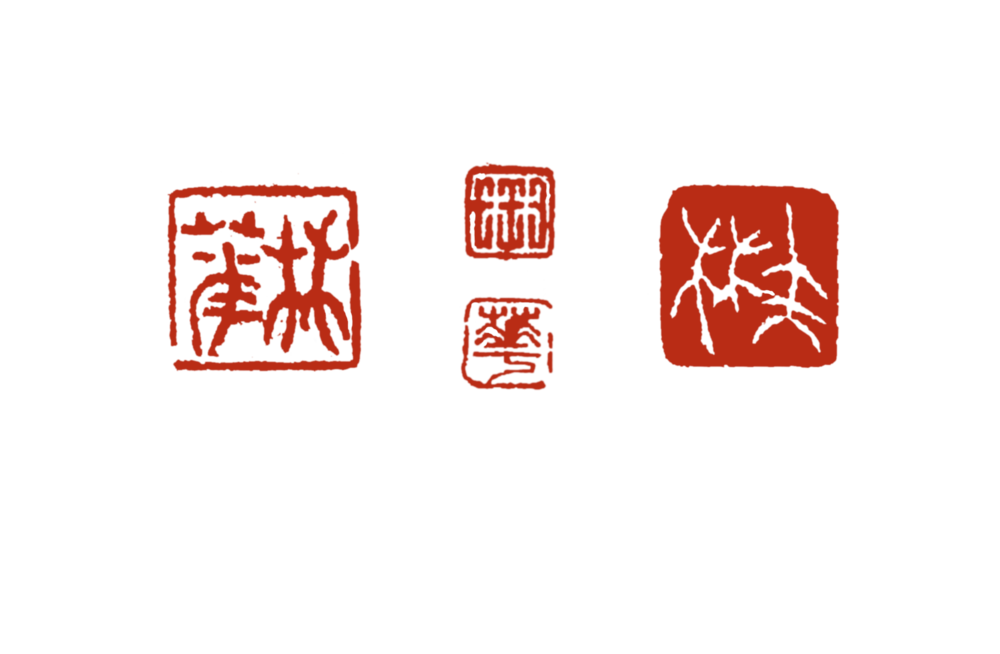

As a Westerner trying to learn traditional Japanese sumi-ink brush painting and traditional Chinese landscape brush painting, I have always striven to learn the techniques of handling the brush and the ink, the rules of composition, the meanings of the subject matter, the styles of famous painters through history, the cultural mind-set of the art form -- all in an attempt to produce work that is faithful to its origins. Many people have commented that they experience my work as truthful and genuine -- I think what they mean is that I have captured and conveyed the mood and feeling of traditional sumi-ink brush painting. Still, I have come to appreciate how far from my reach the goal of absolute authenticity remains. I did not pick up a traditional brush until I was in my 20s; I did not grow up surrounded by traditional Asian images and composition; I did not absorb, beginning in childhood, the mind-set of traditional Asian art as part of my personal world-view.

At first I was disheartened to realize how far I was from my goal of cultural credibility in my work. Then I realized that art always has been cultural syncretic art, and today this is truer than ever before. Rather than expunge my Western art qualities, I decided to embrace my differences. Now instead of erasing my unique vision, I express it by blending my Western persona with the skills, materials and mind-set of traditional ink-brush painting. My art is strongest and most complete when I fuse both cultures -- Western and East Asian.

While I continue to learn as much as I can about the traditional forms and skills which are the basis of East Asian brush painting, I am also exploring new applications of these mixed with Western imagery, informed by Western values and taste. I am consciously and happily creating my own version of cultural fusion art.