Every material and immaterial expression of a culture embodies and communicates the values of that culture. We can begin to understand and appreciate Chinese brush painting - an important part of classical Chinese material culture - by examining the ways in which it incorporates the values found within Taoism and Confucianism. Brush painting fuses these two philosophies, harmonizing and reconciling them. Brush painting is at once bound by rules and also requires freedom and imagination; it captures the naturalistic world through expressing an idealistic world-view; it is firmly rooted in tradition yet must be original to each artist.

Taoism contributed to the painters’ world view by emphasizing that there is a spirit, a moving power which is part of all objects and gives them their identity. This animating energy is called “ch’I” or “qi” - the aliveness or life breath that is in everything. A brush painting must manifest this spirit. For example, to a Westerner, a rock is inanimate and inert; to the Chinese it is a living thing. The manual of painting called The Mustard Seed Garden, published around 1700, describes how to paint rocks by saying that one would never paint a rock without ch’I. Without the vivifying spirit of ch’I the rock would be dead, dry and bare. Painting rocks with ch’I must be sought beyond the material and the tangible. The form of the rock must be clear in the painter’s heart and mind, and thus its expression lies within the artist. Classical Chinese brush painting relies on the painter’s mind to make manifest in material form the ultimate creative principle in the universe. By doing this, both painter and viewer are connected to this living force.

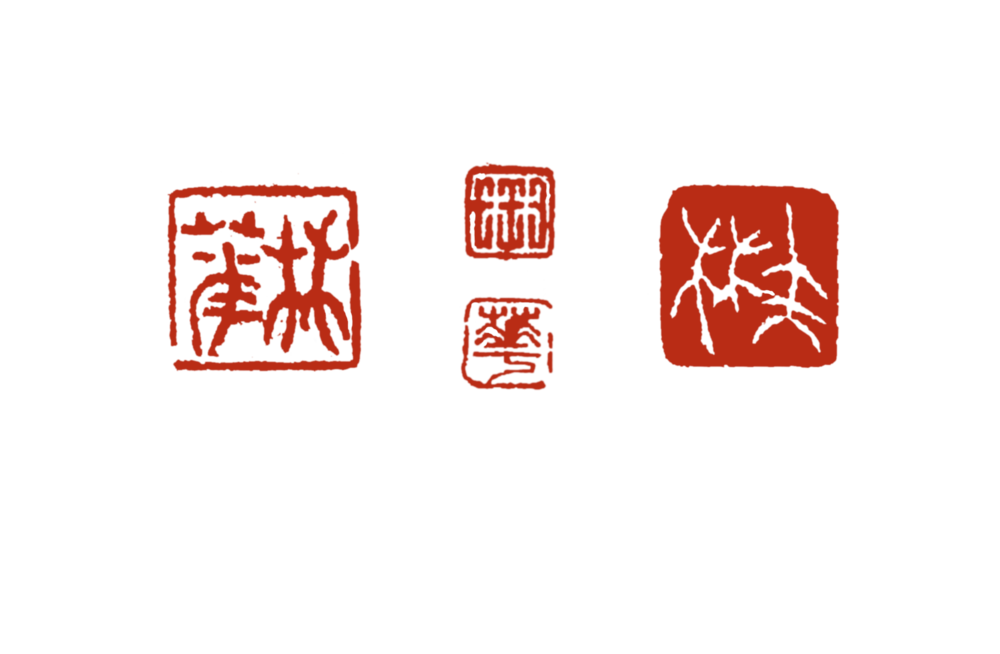

Confucianism, on the other hand, was concerned with the here-and-now; it presented the basic principles which guided social order. Only through conformity to these principles, moderation, and inner strength, could social and personal chaos be avoided. The Confucian ideal was cultivation of the higher self, resulting in the natural elegance of a learned and disciplined scholar who avoided commonness and vulgarity. The Confucian-trained painter was well-read and well-traveled, able to gain the wisdom of the ancients through extensive learning and diligently following the tried and true rules. Painters were scholars, part of the state-supported intellectual aristocracy which embodied the best of Chinese civilization. At the same time they were enjoined to be humble, free from craving for personal fame. They said much with very little, seemingly effortless in exercising their art. They were “ama-teurs”, painting for love of the activity and what it meant, not for commerce. Within themselves, the scholar artist reconciled contradictory values: they were celebrated for being spontaneous and eccentric, expressing a personal character, but they had to do so without straying outside the traditional bounds of the cultivated gentleman. They were required to find their own style, but only after exploring all the styles which had come before. The scholar-painter represented a harmonizing of freedom and tradition, furthering the stability of the state without letting it become static. Scholars learned about and furthered the Confucian virtues by studying the paintings of those who had come before them and producing their own contemporary versions which would, in turn, be studied by those who came after them.

These comments were inspired by the basic text of Chinese brush painting available to us today, The Mustard Seed Garden (1700), and by Principles of Chinese Painting by George Rowley (1974).